You have probably heard reference to the Protestant Work Ethic, an attitude toward work characterized by a pioneer in the field of Sociology, Max Weber (The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism). It’s an attitude, which Weber saw exemplified in Calvinism and most fully manifested in America. It regards work as a moral virtue, valorizes hard work, and with equal vigor it judges idleness and dependency.

It’s a harsh ethic that became a pervasive theme in the mythology of the self-made man and American meritocracy. But my purpose here is to address the way in which excess can be avoided and a properly positive regard for work and achievement can be preserved. What will help us notice when our approach to work, even hard work, has become unhealthy and has generated patterns of compulsive overwork?

The Effects of Overwork

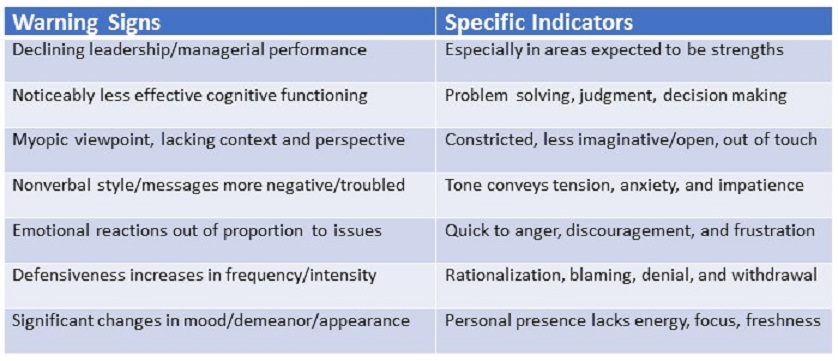

One answer to this question consists in noticing signs of deterioration in our behavior, emotions, and overt performance at work. The table below summarizes some of the ways overwork can undermine our effectiveness in the workplace. Implicit in these specific warning signs is evidence of fatigue that may become a rather common theme of complaints in your conversation with significant others. The fatigue is caused by growing levels of stress and strain, which increase even more quickly as our coping resources and resilience are depleted. It cuts deep and becomes more difficult to recover and feel recharged after a long weekend.

Better Ways to Cope

What is described above is a chronic pattern of overwork. The chronicity of this pattern can easily signal to us that something more fundamental is at issue, i.e., our competence, our character, our hopes for career success. Wow! That can breed feelings of desperation and vulnerabilities to act impulsively. By this time, we have lost our internal locus of control. We feel that we are at the mercy of circumstances.

Indeed, there may be something more fundamental at issue, but it’s less likely to be a flaw in our basic abilities or moral character than it is an unmet need to learn from our experience. One of the simplest solutions to this problem is a shift in attitude, to suspend our reactive fears and insecurities and become curious about what our experience (physical sensations, rational observations, feelings) are teaching us.

It is almost always the case that others have already noticed. They can see that we are no longer the healthier version of ourselves. So, there is little to lose in owning the fact that we are approaching burnout and need to get some fresh perspective on how to adapt and adopt a more sustainable approach to work. Your supervisor and/or your significant other may be a good starting point.

Among the more common recommendations I encourage people to explore is finding their proper maintenance cycle. Each of us as individuals and as couples, given our circumstances and the demands of our career, will usually benefit from periodic times of rest and renewal. For some of us it may be every 6-8 weeks, for others it may be every 3 months. But it is usually more frequent than we currently believe it is. These breaks can vary in length, but they should be planned times of being totally unplugged.

Another recommendation is to be more mindful of how you start your day and how you end your day. We can all usually design a way of starting our day that leaves us feeling less put-upon and rushed, even if that start-up routine is brief. Similarly, at the end of the day we can usually find a way to decompress from the emotions of the workday and transition to the moment of rejoining our family or significant other. If you need help in reshaping these patterns, find someone to talk to – it’s healthy and adaptive.