And How Is That Working For You?

“When we are unhappy with how things are turning out, we must change our behavior, for the way things are turning out is a result of the behaviors we are currently using.”

It’s a simple assertion, one that is much simpler said than done. Why? Because we grasp hold of habitual ways of seeing, thinking, and doing with all the tenacity of a true believer. Even when these habits leave us falling short of what we want repeatedly and failing in areas of life that we deeply care about succeeding in, we cannot let go of them … at least that’s the way it seems.

What’s the solution? It involves relational learning, which means learning in a relationship with another person. It’s a relationship within which we are awakened to our habits, presented with opportunities to make informed choices, and learn how to act on them. Now, you might ask, “Is that therapy or is that coaching?” That’s for another day. In either case it’s adaptive development.

Not Another Theory of Change!

No, it’s a theory of learning, which is usually the most adaptive response to change, especially when the change concerns disappointing results. Learning concerns knowledge of (self, others, situation) and knowledge about (matters of fact methods, procedures), as well as skills to act from that knowledge. That is to say, what we’re talking about is the acquisition of accurate and useful knowledge, and relevant and effective skills. They prove to be accurate and effective when put to use in practice - they work!

That sounds so neat and tidy, doesn’t it? But when we’re stuck, and when we’ve tried and tried to solve our problems, to figure things out, to learn, all without success, it does not look or feel very neat and tidy. We’re frustrated, discouraged, and our attitude and energy move in the negative direction. We know at some level it’s not because we’re stupid, but we can’t help feeling less able and smart.

The thing we need to remember – phrased a bit differently than our opening quotation – is that what we have learned is not working. And it’s not simply not working, it is interfering with our ability to learn new ways of functioning. That’s a good definition of “self-limiting.” Therefore, the first thing we must do is to question and unlearn the stuff – thoughts, feelings, patterns of action – that are problematic. And keep in mind, that the learning we seek is situation specific.

Our habits became automatic ways of navigating our social and practical environment because they worked. But what was enough there and then is obviously not the right approach here and now. So, where do we begin this learning process? We begin with a concrete description of a current situation that is not working. The situation that can be described as a “slice of time.”

Situation Analysis

Tom is having trouble getting things done in his new role as team leader. Here’s the way he describes a specific example: We all arrive in a meeting room for a project review. I try to call the meeting to order and get things going, but others can’t stop their conversations. So, I put my foot down. But then everyone goes quiet and I can’t get people to be really engaged in figuring out the problems we need to solve.

I asked Tom, “How did you interpret this situation as it played out?” His response was kind of rambling: I was pissed off, frustrated. They know me, and they know this is important work, so why don’t they give me a break. I would never have taken this job (promotion) to lead this group if I knew they were going to pull this kind of “stuff” (expletive deleted)!

“So,” I asked, “what did you do?” He responded: It was like pulling teeth, but I just went directly to them with questions about their ideas and recommendations. We came out with something that was okay, but it was much more difficult than it needed to be. Afterward, I asked one of the people, Hallie, “What that was all about?” She said that they got carried away getting caught up on their holiday experiences, and then felt I was really in a bad mood.

“So, Tom, did you get what you wanted?” His face flushed with frustration: Yes and no. That’s not the kind of leader I want to be. And we may have done okay with the work, but I don’t think we’ll do our best work that way. And I don’t like being seen in a negative light, you know, the bad mood thing.

Take Two

I heard him, what he voiced and the feelings that were not spoken. “Well, how about if we go through this situation again and try to notice how it might work out differently the next time?” No surprise, Tom was all in. And as we processed the situation, we considered different ways we might interpret their behavior, and different actions he might have taken to get what he wanted from the meeting.

We did this in the context of a trusting relationship. I even shared my personal sense of the “serious edge” that he may at times signal with his facial expressions. We discussed how that might arise from his intense worries about “getting it right” and “proving himself.” He discovered that if we could talk about these matters openly, that he could probably express his feeling more openly with his team too.

The role is new. He wants to succeed. He wants to work together with the team as they always have, with some playful back-and-forth, but also with and real sense of pride in getting the job done. And it’s different figuring out how to do that as a leader. That’s what he did. They talked about it. He became less self-conscious about playing his role, calling the meeting to order without getting “cranky.”

Situation Analysis: Take Two

In a world that thrives on action and problem solving, timeliness is prized. Adages like “don’t let the perfect be the enemy of the good” normalize an urgency to act with approximate accuracy and good-enough effectiveness. But what happens our situation analyses are rushed, episodic, and involve few if any "second takes?"

When a group of “cooler heads” prevail, their fact-based, analysis of problem situations or opportunities often succeed. Sound methods and practices for such analysis have been developed and are taught in business schools. Most rely on data gathering, quantitative analysis, and some sort of deliberation, scenario planning, and practical judgment.

Still, more than 50% of new businesses fail within two years, 40-60% of new hires depart the hiring company within 18 months, and the majority of process improvement initiatives and M&A investments fail to achieve their aims. So, our methods are not perfect, and anything that can improve their success deserves our attention, even if it stems from the “soft” science of psychology.

Situation Analysis & Particularity

In business, situation analysis is an established means of guiding judgment on strategic action and on vital tactical decisions. Here’s one definition of situation analysis:

The systematic collection and study of past and present data to identify trends, forces, and conditions with the potential to influence the performance of the business and the choice of appropriate strategies. The situation analysis is the foundation of the strategic planning process. The situation analysis includes an examination of both the internal factors (to identify strengths and weaknesses) and external factors (to identify opportunities and threats). It is often referred to by the acronym SWOT. (American Marketing Association)

What goes less noticed in business methods is the role of interpretation. Facts and data don’t really explain themselves. And models and theories intended for explaining things in general don't really explain this or that situation in particular. Particularity, after all, refers to unique, case-specific, qualities of an individual person, situation, or experience.

And it is interpretation that we rely on when seeking to understand the unique features and causal influences that explain something we wish to understand with particularity. In the field of action, we shape our strategy to this particularity. Particularity concerns the minute details “out there” that we might observe with a second “take.” It also consists in seeing them as other stakeholders see them.

We are among the stakeholders, aren’t we? So, particularity implies a meta-awareness of our own and others’ perceptions, thought, feelings, strivings, practical interests – these are the lenses through which we see the particulars that differentiate our situation. We do so by suspending judgment, loosening the grip of urgent drives and desires. We then see the situation as it really is, not as some mere objectivity, but as a multi-faceted relatum.

Particularity concerns the way a situation is given to us in experience, but it includes the other ways it might be given to us too. Thus, seeking an accurate and sufficient grasp of particulars in a specific situation involves a special rigor in seeing things. It gives us better insight into how what is seen may be relevant to the motivations, aspirations, and purposes of the stakeholders involved.

Eliciting Particularity

First, we must summarize the situation as we observe it to be. Let’s take an example of problematic change: The VP of Marketing for ABC Company informs our agency by email to halt all service delivery on a multi-media promotional initiative. The account executive, Eric, shares the news with his boss, and the request for information begins, “We can’t lose this business!”

That’s what happened. Is there more to the story? Probably, but Eric is having difficulty getting further information. So, how does he interpret the situation? The VP is playing it close to the vest, which is not characteristic of her. Eric is accountable for this as Q4 revenue: “My superiors don’t like bad news.” Thus, Eric asks the client if there’s anything he can do to keep the business - “issues we can resolve?”

The client says “no,” there’s no way it can be changed. After informing his boss, Eric is called into a meeting with senior management. He was anxious. Some of them were too. The COO broke the silence, “Look, this is an anchor client. We need to retain the revenue, but, even more, we need to retain the client. So, let’s see if we can sort this out.” His tone was calm.

He continued, “Tell me more about the situation, Eric.” This was enough to calm Eric a bit. His COO signaled to the group a norm of composure and care. Eric said that the client had gone quiet the past few weeks while Eric was spending his time trying to close 4th quarter sales. Then this news broke. They soon concluded that something had gone awry, but further pressuring Eric was not the answer.

They wanted was to retain the client, but their actions had served to neglect communications with the client. Historically, their business grew with this client as the trust and intimacy of the relationship had grown. What kept them in the inner circle of service providers was their direct relevance to the client’s priorities. These kinds of interpretations produced working hypotheses and next steps.

Take Two

Actions and strategies, including those for account management, emerge from a particularistic kind of situation analysis and planning. An essential fact about particulars is that they change. External factors change and affect factual particulars, and internal factors change that affect perceptions. We cannot know how these factors change and influence our client unless we “travel” with them.

That’s the true mark of intimacy. We know the clients with whom we have intimacy in their particularity as a company, as managers, and as people trying to thrive. A good situation analysis is a snapshot based on take-two perceptions and interpretations of the particulars that inform adaptive change for our clients and that inform our strategies and practices for serving them.

Mature Mind & Positive Influence

In those moments when we feel least effective and most frustrated, and especially when this experience becomes chronic, we’re aware of how it steals our capacity to get things done. Something has happened and continues to happen in our mind. It's not working as well as we’d like it to. We’re exhausted, perhaps irritable or indifferent, but certainly not positively charged. Our thinking is dulled, our judgment is compromised, our imagination and repertoire of problem-solving skills seem to have left us. And it’s not just us; we seem unable to connect and influence others in any positive way. This is not what we want. We’re stuck. We want change. And change can happen. That’s what I discuss in my latest whitepaper.

.

Are You Growing as a Leader?

Exciting Growth at the Intersection of Person and Role-Taking

Some of our most dramatic gains in leader development owe much to identity growth spurts, which occur in the course of facing new challenges. They are effortful, sometime even painful, breakthroughs that transform our ways of thinking, feeling, and relating. They’re occasioned by the felt demands of the roles we take. The demands are more than a call to action, they’re a call for adaptive learning about self, situation, and what we must do differently in order to thrive.

Are you or someone you care about at this intersection of growth? Its arrival is accompanied by feelings of exhilaration and exhaustion, high hopes and perilous fears. It usually includes a pervasive sense that much is at stake, and that we have a significant opportunity to make a difference. Beyond the elation over “upsides” lie a sobering burden of responsibility, often more felt than fully understood. What can we do to make the most of this opportunity and fulfill its responsibilities?

Those are the questions I discuss in this article.

The Effects of Challenge

From infancy forward, there is within each of us an inherent curiosity and striving to be, to explore, to experience, and to orient ourselves in our surrounding world. We do not do this alone; it’s always within a social context and in the company of others who reflect back to us what they see in us. With the best of parenting, teaching (school years), and supervision (in vocational life), we find encouragement in the responses of others as they recognize and affirm our insights and evolving competencies as persons.

In that way, we become known to others and to ourselves as independent centers of awareness with a capacity for intelligent adaptive action. A growing sense of our personal potential to initiate purposive action (agency), and to do so in ways that genuinely express our interests and preferences (personality) constitute core elements of our identity (unique self). And as we cultivate a mature attunement to our normative framework of moral beliefs about what is good, right, and proper, self-identity deepens.

Figure 1. The Challenge-Development Curve

This all occurs, of course, as we navigate the school years, post-secondary education, and early career experience. At some point, our challenges become less about individual task-oriented, practical abilities, especially as we aspire to manage and lead others. Then, challenges become more complex, our success becomes increasingly contingent upon the way we get work done through others. Cognitive, emotional, and relational aspects of working together co-determine our efficiency and effectiveness.

Those who seek careers in management tend to be achievement oriented. Presenting them with new or bigger problems or opportunities will typically represent a powerful stimulus for creative-productive action. It will intensify their focus and efforts – cognitive, emotional, and practical. As illustrated in Figure 1, rising levels of challenge will stimulate learning and gains in our capacity to perform…that is, up to a point (A-B). Beyond the inflection point we not only observe diminishing returns but actual declines in our capacity to perform.

This downward spiral (decompensation) is usually the result of accumulated stress, strain, and fatigue. These effects can build insidiously, just as the boiling-the-frog metaphor suggests. Although it may feel we are suffering these effects privately, it is others who will often first notice their adverse impacts, and not just at work. It’s often those closest to us who witness our unvarnished emotional reactions and our insistent assertions that we’ll get a handle on it.

Plotting Our Position on the Curve

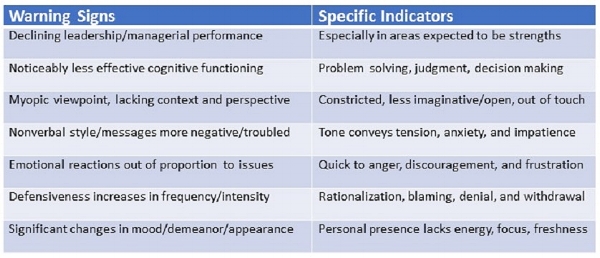

As you scan Table 1, I am confident that some of the “warning signs” will be familiar, because you’ve been there yourself or because you’ve observed them in others. Most of us with confidence and a track record of “playing through pain” will rationalize, minimize, or deny feeling stuck. It will be embarrassing to acknowledge that our coping efforts are failing, that our struggles are affecting others. In the best of circumstances this defensive routine is shorter in duration, it’s almost never nonexistent.

Table 1. Warning Signs of an Approaching Inflection Point

The most important reason to specify the warning signs of an approaching inflection point is to prompt attentiveness. By noticing these signs earlier, we are more able to come to grips with them in a timely and effective manner. Timely intervention, as illustrated in Figure 2, requires a “reflective pause” and perspective-taking at just the time when our focus is narrowing and intensifying. Feelings of desperation are beginning to activate defenses and close off our access to adaptive avenues of action.

Figure 2. A Multi-Curve Model of Adaptive Growth

However, with timely intervention, we can change the trajectory of the curve. In fact, we can perhaps facilitate a “jump” to another curve, achieving a more transformative quality of adaptive change and growth. Doing this requires the counter-intuitive use of the reflective pause mentioned above.

You will notice prior to the inflection points B, D, and F in Figure 2 are reflection points B1, D1, and F1. There is a downward dip in the new curve of adaptive development. It represents the pause, pulling our shoulders back from “wheel” for a moment. There is also an outward shift to the right, which indicates capacity growth that is will span even higher levels of challenge.

These are intervention points. The pause provides us with an opportunity to assess the felt the demands of our role afresh. It allows us to appreciate how those demands impinge upon us. In what aspects of the challenge are we finding ourselves overwhelmed, lacking the know-how or capacity to cope?

Although our individual reflection upon these matters may produce valuable insights and possibilities for action, it is the feedback from others, our stakeholders, that will prove especially helpful. It will help us appreciate what only they can see and report from their role and their experience of our presence and behavior. (For more on the vital importance of feedback, see my recent article on the Johari Window.) With increased self-awareness and other-awareness, we are better able to target key gap themes.

Coaching helps us acquire these data, actively and fruitfully process them for insight, and then translate those insights into work-relevant, role-specific development themes. In such “processing” the coach is there to offer a sufficiently tough quality of “love” (self-discovery & encouragement) to ensure that we formulate realistic ideas about what we need to do differently, where to start, and how to include and involve others in the process. After all, why ask for feedback if we’re not going to invite constructive engagement, right?

Conclusions

There’s much more to the process of leader identity development that occurs in the course of adult role-taking. And there is more to the art of being there for those we coach through this vital kind of personal growth. Both merit additional attention. However, one further thought I would leave you with is that of an “Arc of Virtue.” It’s the arc traced by the upward line of movement that intersects the origin of each new adaptive development curve in Figure 2.

I use these graphical illustrations because I hope they can help us better picture the constellation of forces at work in adult development. Knowing these graphics are based upon well-established theory and empirical research, should give us reason for optimism. But to bolster that point, let me share an even more fundamental truth: It is that none of this is out of reach for any of us unless we choose to believe it is beyond us. Don’t make that mistake!

Do You Really Want to Manage?

It’s a common question among early-career professionals, those in the first 5-7 years of their career. But it also arises later for mid-career adults who’ve had a bit of supervisory or managerial experience. And beyond its specific focus on managerial versus non-managerial career options, it symbolizes a deeper inquiry about what we want in life, what motivates us and why, deeper more existential questions.

So, perhaps “want” is the most important word in my title. It points directly to the appetitive dimension of human nature and motivation. And when we consider the more nuanced differences between want and desire, and seeking and striving, we discover the source, meaning, and power of such aspirational themes, how they shape our identity, influence our actions, and produce joy or perpetual restlessness.

Simple Definitions Reveal Complexity

About Wants

To want is to desire, but in a specific sense. It’s a simpler, object-specific desire for something we do not have. Wants arise and are satisfied or not through our acquisition of the wanted object, i.e., chocolate, a car, a pay raise, a promotion, a date, tickets to a concert – things that are external to us as persons. Wants come and go, one after another. They’re discrete felt needs of limited duration.

About Desires

Desires that live beyond the satiation of any one want, that go to our sense adequacy and well-being as a person… Well, that’s a different thing. It’s the full and proper meaning of desire as distinct from want. Its aim is to extinguish deeply felt needs for completion. Its intensity is a craving to fill a hole within us. Its intensity can become desperate, obsessive, especially as it grows outside conscious awareness.

Risks of Confusion

It is in this sense that in Buddhism and in some Western religions, desire can be seen as the root of all suffering and moral failure. It is in this sense also that desire can lead to inauthentic living. For rather than focusing on being, we surrender to an anxious, acquisitive, alienating mode of life called having. We mistake parts for the whole of life. We mistake stuff for growth and self-actualization.

So, want and desire run amok can lead away from love, virtue, growth, and happiness. But they’re also inherent to our nature. They energize our being and need not run amok, lead to harm and unhappiness. When we attend to and notice the wants and desires that define our appetite and actions, we can choose to examine them with an attitude of curiosity. We can learn!

Wisdom from Reflection

Something as ostensibly practical and compartmentalized as the question of whether or not I really want a career in management can lead to more fundamental questions. Notice how these questions arise from troubled feelings, in moments of suffering. Wants and desire are felt and acted on long before they consciously or cognitively known. Their life predates our verbal and cognitive abilities.

Some Classic Wisdom

The words of a famous 17th century philosopher, Spinoza, are relevant here: “The endeavor, wherewith everything endeavors to persist in its own being, is nothing else but the actual essence of the thing in question.” (From his Ethics) Our vital endeavors to be can run amok. We are imperfect creatures. and we are moved by two kinds of emotion according to Spinoza, those linked to actions and passions.

Actions are purposive endeavors, conscious and guided by considered judgment. Passions are aroused or excited by things and experience external to us. They may arouse positive feelings, elevated emotions of wonder, compassion, and love. However, when they operate without the mediation of mind, they can also arouse baser fears and reactive acts of avoidance or aggression.

Practical Take-Aways

It is our relationship to the feelings that arise in life that is most vital. Thus, asking what I want and why I want it raises to consciousness the aims and meaning that our strivings hold for us. What is it that seems so important? What is it that this desire signals about me and what I need? In this way, some desires are extinguished (as false goods), others reframed as wants or transformed into something less intense.

We now more easily appraise the relative importance of the values that underlie our appetitive strivings. We gain emotional freedom and make informed choices about life goals and career goals. Our strivings are aligned – and they’ll need to be repeatedly aligned – with aims of virtue and happiness. Always more difficult in reality than in thought, and always made easier in conversation with those we trust.

-

December 2023

- Dec 18, 2023 Are You Working Too Hard? Dec 18, 2023

-

October 2023

- Oct 2, 2023 The Power of Empathic Notice Oct 2, 2023

-

January 2023

- Jan 19, 2023 A Five-Step Pathway to Positive Attitude Jan 19, 2023

-

November 2022

- Nov 4, 2022 Resentment and Ressentiment Nov 4, 2022

-

July 2022

- Jul 19, 2022 Overcoming Resentment Jul 19, 2022

-

February 2022

- Feb 28, 2022 What Does it Mean to Express Our Feelings? Feb 28, 2022

-

October 2021

- Oct 18, 2021 Coping is More Than Acceptance Oct 18, 2021

- Oct 13, 2021 Loneliness Oct 13, 2021

-

September 2021

- Sep 25, 2021 Opposites Attract … and They Fight Sep 25, 2021

-

August 2021

- Aug 13, 2021 Coping With Negativity Aug 13, 2021

-

May 2021

- May 23, 2021 Relationships and Emotional Truth May 23, 2021

- May 3, 2021 Meeting Others as Persons May 3, 2021

-

April 2021

- Apr 23, 2021 Apologies Apr 23, 2021

- Apr 5, 2021 Change, Motivation, and Practical Wisdom Apr 5, 2021

-

March 2021

- Mar 2, 2021 Learning to Lead Mar 2, 2021

-

February 2021

- Feb 7, 2021 Whence Cometh Virtue? Feb 7, 2021

- Feb 6, 2021 Escaping Isolation Feb 6, 2021

- Feb 4, 2021 Executive Function Feb 4, 2021

- Feb 2, 2021 Moments of Meeting Make a Difference Feb 2, 2021

-

January 2021

- Jan 28, 2021 Mood, Emotions, and How to Deal with Them Jan 28, 2021

- Jan 24, 2021 Leadership, Purpose, & Values Jan 24, 2021

- Jan 18, 2021 Leadership in a Post-Trump Era Jan 18, 2021

- Jan 11, 2021 Improving Relationships Jan 11, 2021

- Jan 5, 2021 3 Steps to Reach Your Goals in 2021 Jan 5, 2021

- Jan 3, 2021 Needs in Development: Therapy, Relationships, and Redemption Jan 3, 2021

-

December 2020

- Dec 23, 2020 “Measure twice, cut once.” The Carpenter’s Motto. Dec 23, 2020

-

November 2020

- Nov 19, 2020 Positive Purpose: Antidote for Chronic Interpersonal Conflict Nov 19, 2020

- Nov 15, 2020 A Couples Competency: Being Friends Nov 15, 2020

- Nov 8, 2020 Learning to Let Go Nov 8, 2020

-

October 2020

- Oct 29, 2020 About Metaphysics and Mind: Why We Should Care Oct 29, 2020

- Oct 12, 2020 Peace and Conflict: Reciprocal Forces Oct 12, 2020

- Oct 6, 2020 Job Crafting as Gateway to Vocational Development Oct 6, 2020

-

September 2020

- Sep 6, 2020 Awaiting Liberty: The American Caste System Sep 6, 2020

-

August 2020

- Aug 24, 2020 Job "Crafting" - Little Changes Can Improve Fit Aug 24, 2020

- Aug 17, 2020 Human Beings: The Angry Species? Aug 17, 2020

- Aug 14, 2020 Irritability and Tension, What's it Telling You? Aug 14, 2020

- Aug 13, 2020 Ruminating too much? Schedule your worries! Aug 13, 2020

- Aug 10, 2020 Positioned to Lead - At All Levels Aug 10, 2020

- Aug 8, 2020 Identity as Integration Aug 8, 2020

-

July 2020

- Jul 30, 2020 What is the Virtue of Work? Jul 30, 2020

- Jul 21, 2020 Parents: Making Self-Care a Priority Jul 21, 2020

- Jul 20, 2020 In the Market for a New Job? Jul 20, 2020

- Jul 18, 2020 Psychologically-Based Coaching Jul 18, 2020

- Jul 12, 2020 The Nobility of Vocation Jul 12, 2020

- Jul 9, 2020 We Shape Our World Jul 9, 2020

-

June 2020

- Jun 28, 2020 Revealing Worries Helps Jun 28, 2020

- Jun 20, 2020 In the Heat of the Moment Jun 20, 2020

- Jun 5, 2020 Attitude Jun 5, 2020

- Jun 3, 2020 In Praise of Passivity Jun 3, 2020

- Jun 1, 2020 Focus on Career Jun 1, 2020

-

May 2020

- May 30, 2020 Active Listening and Intimacy May 30, 2020

- May 27, 2020 Tolerance for Intense Emotions May 27, 2020

- May 21, 2020 Getting it Right and Getting it Done May 21, 2020

- May 19, 2020 Coping with COVID & Adaptive Change May 19, 2020

- May 9, 2020 What Are Data? May 9, 2020

- May 2, 2020 Concepts and Intuition: Two Ways of Knowing May 2, 2020

-

April 2020

- Apr 25, 2020 Emotional Dysregulation in the Pandemic Apr 25, 2020

- Apr 22, 2020 Experience Arrives Unbidden Apr 22, 2020

- Apr 17, 2020 Evocative Stimuli for Growth and Change Apr 17, 2020

- Apr 15, 2020 Morning Hours Apr 15, 2020

- Apr 14, 2020 Innovation versus Opportunism Apr 14, 2020

- Apr 10, 2020 Verstehen, Empathy, and Motivation Apr 10, 2020

- Apr 8, 2020 Are You Getting Grumpy? Apr 8, 2020

- Apr 5, 2020 5 Reasons to Talk to a Therapist During the Pandemic Apr 5, 2020

- Apr 1, 2020 The Other Sympathetic Response System Apr 1, 2020

-

March 2020

- Mar 26, 2020 Virtual Meetings on Big Ideas Mar 26, 2020

- Mar 18, 2020 Life, Self, and Action - even during COVID 19 Mar 18, 2020

- Mar 17, 2020 Growth Occurs in Spurts: Are You Ready? Mar 17, 2020

- Mar 12, 2020 Making Video Connections Work Mar 12, 2020

- Mar 10, 2020 Are You Neurotic? Mar 10, 2020

- Mar 9, 2020 Do You Use Your Smile? Mar 9, 2020

- Mar 7, 2020 The Freed Group and Team Mar 7, 2020

- Mar 5, 2020 Being There Mar 5, 2020

- Mar 4, 2020 What's Next? (career, relationships, self-discovery) Mar 4, 2020

- Mar 2, 2020 A New Angle on the “Who Am I?” Question Mar 2, 2020

-

February 2020

- Feb 28, 2020 Everyone Wants to Manage, Right? Feb 28, 2020

- Feb 25, 2020 Discussion & Dialogue: Their Distinct Purposes Feb 25, 2020

- Feb 19, 2020 Too Soon Old Feb 19, 2020

- Feb 14, 2020 Freedom: Organism as Person Feb 14, 2020

- Feb 5, 2020 Interviewing: Candidate as Collaborator Feb 5, 2020

- Feb 2, 2020 Coping With Persistent Anxiety Feb 2, 2020

-

January 2020

- Jan 28, 2020 Depression or Despair? Jan 28, 2020

- Jan 20, 2020 Does One's Personality Change? Jan 20, 2020

- Jan 13, 2020 Criticism, Positive or Negative? Jan 13, 2020

- Jan 12, 2020 Anger Jan 12, 2020

- Jan 6, 2020 Making Couple’s Therapy Work Jan 6, 2020

-

December 2019

- Dec 31, 2019 A New Existentialism Dec 31, 2019

- Dec 26, 2019 Emotional Meaning ≠ Emotional Intelligence Dec 26, 2019

- Dec 18, 2019 The Importance of Emotional Meaning Dec 18, 2019

- Dec 16, 2019 Motivation as Moving Cause Dec 16, 2019

- Dec 13, 2019 Effective Interpersonal Presence: How We Get There Dec 13, 2019

- Dec 11, 2019 When Loneliness is Fear Dec 11, 2019

- Dec 9, 2019 The Myth of a "Private Me" Dec 9, 2019

-

November 2019

- Nov 26, 2019 Good Me, Bad Me, Not Me Nov 26, 2019

- Nov 17, 2019 Sustaining Adaptive Change Nov 17, 2019

- Nov 15, 2019 Formation of Self & Adaptive Change Nov 15, 2019

- Nov 14, 2019 Attention: Guiding Force of Freedom Nov 14, 2019

- Nov 8, 2019 Intentions & Acts: Vital Aspects of Change Nov 8, 2019

- Nov 4, 2019 What's Mental about "Mental" Models? Nov 4, 2019

-

October 2019

- Oct 25, 2019 Coaching: A Brief 6-Week Model Oct 25, 2019

- Oct 23, 2019 How Love Solves Problems Oct 23, 2019

- Oct 11, 2019 On Being the Youngest Oct 11, 2019

- Oct 9, 2019 Procrastination and Self-Forgiveness Oct 9, 2019

- Oct 7, 2019 Cardinal Themes: Assertiveness and Honesty Oct 7, 2019

-

September 2019

- Sep 22, 2019 Personal Impacts of Sociopolitical Chaos Sep 22, 2019

- Sep 19, 2019 Telling Lies and Telling Stories: Sep 19, 2019

- Sep 16, 2019 The Nature and Nurture of Kindness Sep 16, 2019

- Sep 7, 2019 Finding the Words Sep 7, 2019

- Sep 4, 2019 Helping One Another Through Conflict Sep 4, 2019

-

August 2019

- Aug 28, 2019 A Powerful Interpersonal Model Aug 28, 2019

- Aug 27, 2019 Generative Dialogue Aug 27, 2019

- Aug 26, 2019 Coping with Conflict & Changing Habits Aug 26, 2019

- Aug 18, 2019 Practical Meditations for a Sabbath Day Aug 18, 2019

- Aug 15, 2019 Generating Positivity at Work Aug 15, 2019

- Aug 5, 2019 Career Coaching at Midlife Aug 5, 2019

-

July 2019

- Jul 25, 2019 Trying Too Hard: A Control Issue Jul 25, 2019

- Jul 14, 2019 Supervision as Super∙Vision Jul 14, 2019

-

June 2019

- Jun 28, 2019 Being Lonely and Being Alone Jun 28, 2019

- Jun 15, 2019 A Tale of Tears: Manager as Ethnographer Jun 15, 2019

- Jun 11, 2019 Assertiveness as Transparency Jun 11, 2019

- Jun 2, 2019 You Never Listen! Jun 2, 2019

-

May 2019

- May 23, 2019 Executive Presence: A Short Course May 23, 2019

- May 21, 2019 Affection, Reflection, Responsibility May 21, 2019

- May 12, 2019 When We Get Frustrated May 12, 2019

- May 11, 2019 The Tethers We Choose May 11, 2019

- May 8, 2019 For Leaders: Emotions & Judgment May 8, 2019

- May 2, 2019 On the Fence About Coaching? May 2, 2019

-

April 2019

- Apr 26, 2019 A Practice Idea: Notes to Clients Apr 26, 2019

- Apr 22, 2019 Relationships: Independence, Interdependence, & Intimacy Apr 22, 2019

- Apr 18, 2019 Trust: A Fragile Thing Apr 18, 2019

- Apr 16, 2019 Authenticity: More Than Individuality Apr 16, 2019

- Apr 12, 2019 Are You an Emerging Leader? Apr 12, 2019

- Apr 11, 2019 Making Difficult Personnel Decisions Apr 11, 2019

- Apr 8, 2019 3 Reasons to Care About Generativity Apr 8, 2019

- Apr 5, 2019 In Pursuit of Coaching Apr 5, 2019

- Apr 4, 2019 Adaptive Intelligence: 5 Tips Apr 4, 2019

- Apr 2, 2019 Leadership, Self-Interest, and Morality Apr 2, 2019

-

March 2019

- Mar 31, 2019 Does Brief Coaching Work? Mar 31, 2019

- Mar 27, 2019 Coping with Infidelity in Professional Couples Mar 27, 2019

- Mar 12, 2019 Using 360 Feedback to Improve Mar 12, 2019

-

February 2019

- Feb 22, 2019 Assessment as Stimulus Feb 22, 2019

- Feb 15, 2019 Is Your Boss in Your Way? Feb 15, 2019

- Feb 12, 2019 Psychotherapy or Coaching? Feb 12, 2019

-

January 2019

- Jan 15, 2019 Confidence in Professional Couples Jan 15, 2019

- Jan 6, 2019 Getting Away and Coming Home Jan 6, 2019

- Jan 5, 2019 The Interpersonal Circumplex Jan 5, 2019

- Jan 2, 2019 Anger as Avoidance Jan 2, 2019

-

December 2018

- Dec 26, 2018 On Trusting Your Gut Dec 26, 2018

-

November 2018

- Nov 25, 2018 People, Planet, & Profit – The Triple Bottom Line Nov 25, 2018

- Nov 21, 2018 And How Is That Working For You? Nov 21, 2018

- Nov 20, 2018 Situation Analysis: Take Two Nov 20, 2018

- Nov 11, 2018 Mature Mind & Positive Influence Nov 11, 2018

-

October 2018

- Oct 21, 2018 Are You Growing as a Leader? Oct 21, 2018

- Oct 14, 2018 Do You Really Want to Manage? Oct 14, 2018

- Oct 4, 2018 Fear as a Call to Action Oct 4, 2018

- Oct 3, 2018 Adaptive Development Oct 3, 2018

-

September 2018

- Sep 23, 2018 On Destructive Leadership Sep 23, 2018

- Sep 19, 2018 Bridging Differences in Conversation Sep 19, 2018

- Sep 17, 2018 Sleep and Effectiveness Sep 17, 2018

- Sep 13, 2018 We Are Not Merely Homo Sapiens Sep 13, 2018

- Sep 11, 2018 Making and Keeping Commitments Sep 11, 2018

- Sep 8, 2018 Connecting Hard & Soft in Practice Sep 8, 2018

- Sep 6, 2018 Destiny Guided by a Calling Sep 6, 2018

- Sep 2, 2018 On Responsibility: John McCain & Henry Bugbee Sep 2, 2018

-

August 2018

- Aug 29, 2018 Social Comparison & Ressentiment Aug 29, 2018

- Aug 19, 2018 Simple Tips to Boost Team Performance Aug 19, 2018

- Aug 17, 2018 Stress: Different for Professionals? Aug 17, 2018

- Aug 11, 2018 Restraint as Presence: How it Positions us to Lead Aug 11, 2018

- Aug 9, 2018 Stress, Strain & Burnout: What to do? Aug 9, 2018

- Aug 8, 2018 When We “Muscle Through” Aug 8, 2018

- Aug 5, 2018 A Coach's Motto: Measure Twice, Cut Once Aug 5, 2018

- Aug 1, 2018 Self Divided or Self Integrated? Your Choice Aug 1, 2018

-

July 2018

- Jul 29, 2018 Does Gender Still Matter? How? Jul 29, 2018

- Jul 25, 2018 Internal Critics: How they're born and put to rest Jul 25, 2018

- Jul 24, 2018 Size of Self & Leadership Presence Jul 24, 2018

- Jul 21, 2018 A Classic Model of Team Development Jul 21, 2018

- Jul 16, 2018 When is Sponsorship Coercion? Jul 16, 2018

- Jul 12, 2018 "Boredom is a Lack of Attention" Jul 12, 2018

- Jul 6, 2018 Know the Person, Then Solve the Problem Jul 6, 2018

-

June 2018

- Jun 29, 2018 A Rhythm of Connecting & Relating Jun 29, 2018

- Jun 21, 2018 Want Respect? First Respect Yourself Jun 21, 2018

- Jun 12, 2018 What is Customer/Client Centricity? Jun 12, 2018

- Jun 5, 2018 Helping Couples: Because Executives are People Too Jun 5, 2018

- Jun 3, 2018 Assess Your Efficacy on Three Critical Themes in Performance Jun 3, 2018

-

May 2018

- May 23, 2018 Vital Relations: Couples and Colleagues May 23, 2018

- May 21, 2018 Rotations and Stretch Assignments May 21, 2018

- May 18, 2018 Not Needing vs. Not Knowing May 18, 2018

- May 14, 2018 Exhausted from trying too hard? May 14, 2018

- May 8, 2018 From Seeing to Doing May 8, 2018

- May 2, 2018 The Practice of Engagement May 2, 2018

-

April 2018

- Apr 30, 2018 Competence & Care: A Powerful Pair Apr 30, 2018

- Apr 25, 2018 Time for a Change? Apr 25, 2018

- Apr 18, 2018 The Defensive Executive Apr 18, 2018

- Apr 16, 2018 Problem vs. Mystery: A Vital Difference Apr 16, 2018

- Apr 11, 2018 The Fulfilling Expression of Self Apr 11, 2018

- Apr 5, 2018 Welcoming the Hard Stuff Apr 5, 2018

- Apr 5, 2018 The Is and the Ought in Development Apr 5, 2018

-

March 2018

- Mar 29, 2018 Five Principles of Practical Wisdom Mar 29, 2018

- Mar 27, 2018 Leadership Communication: Navigation & Meaning Mar 27, 2018

- Mar 21, 2018 A Leader's Role in Issues of Attitude Mar 21, 2018

- Mar 19, 2018 The Power of Stopping for Starting Mar 19, 2018

- Mar 15, 2018 When being quiet speaks volumes Mar 15, 2018

- Mar 9, 2018 Kindness as Skillful Leadership Action Mar 9, 2018

- Mar 7, 2018 Skillful Speech as Leadership Action Mar 7, 2018

- Mar 4, 2018 In Praise of Ordinary Virtue Mar 4, 2018

- Mar 3, 2018 Three Ways to Boost Proactivity Mar 3, 2018

- Mar 2, 2018 Skillful Action: Three Examples Mar 2, 2018

-

February 2018

- Feb 26, 2018 Making Virtual Coaching Work Feb 26, 2018

- Feb 22, 2018 Getting Real About Performance & Development Feb 22, 2018

- Feb 21, 2018 Buddhist Psychology for Leaders Feb 21, 2018

- Feb 19, 2018 Coaching After Hours Feb 19, 2018

- Feb 16, 2018 On Being an "Imperfect" Buddhist Feb 16, 2018

- Feb 6, 2018 Moods, Attitudes, & Skillful Action Feb 6, 2018

- Feb 2, 2018 Virtual Coaching - It's Your Choice! Feb 2, 2018

-

January 2018

- Jan 29, 2018 Executive Development & Action Learning Jan 29, 2018

- Jan 22, 2018 Development as Enlightened Pragmatism Jan 22, 2018

- Jan 17, 2018 Overcoming Bias: Appraisal of Talent Jan 17, 2018

- Jan 8, 2018 Self-Managing Your Personal Presence in the Boardroom Jan 8, 2018

- Jan 3, 2018 Making Relationships Work Jan 3, 2018

-

December 2017

- Dec 29, 2017 Living the Moral Duty of Leadership Dec 29, 2017

- Dec 15, 2017 Safety & Confidence: Leaders Need Both Dec 15, 2017

- Dec 14, 2017 What Makes Active Listening Work? Dec 14, 2017

- Dec 12, 2017 Why Counting to 10 Works Dec 12, 2017

- Dec 4, 2017 Person as Bridge to the Manager-Leader Divide Dec 4, 2017

-

November 2017

- Nov 27, 2017 Finding & Following the Leading Thread Nov 27, 2017

- Nov 16, 2017 Fear, Self, and Thriving Nov 16, 2017

- Nov 12, 2017 What is Your Vitalizing Practice? Nov 12, 2017

- Nov 7, 2017 Right Speech & Good Leadership Nov 7, 2017

- Nov 1, 2017 Presence and Personal Efficacy Nov 1, 2017

-

October 2017

- Oct 16, 2017 Full-Minded Leadership Presence Oct 16, 2017

- Oct 12, 2017 The Responsibility Discussion in Teams Oct 12, 2017

- Oct 12, 2017 Tapping all the potential of your talent pool Oct 12, 2017

-

September 2017

- Sep 21, 2017 The Social Sources of Self Sep 21, 2017

- Sep 8, 2017 Getting Smart About Stress Sep 8, 2017

- Sep 1, 2017 The Tuckman Model of Team Development Sep 1, 2017

-

August 2017

- Aug 28, 2017 Lower Agreeableness = More Stress Aug 28, 2017

- Aug 25, 2017 Pay it forward coaching Aug 25, 2017

- Aug 23, 2017 Work-Related Stress and You Aug 23, 2017

- Aug 11, 2017 Another Use for Mindfulness at Google Aug 11, 2017

- Aug 6, 2017 Smiling Back at Our Problems Aug 6, 2017

-

July 2017

- Jul 13, 2017 Frustration, Waste, & Personal Performance Jul 13, 2017

- Jul 10, 2017 The 4 T's of Great Relationships Jul 10, 2017

-

June 2017

- Jun 19, 2017 Two Selves, Together and Apart: Practical Consequences Jun 19, 2017

- Jun 8, 2017 On Willing Avoidance Jun 8, 2017

-

May 2017

- May 23, 2017 Behavioral Integrity and Culture Change May 23, 2017

- May 22, 2017 Why we struggle with conflict May 22, 2017

-

April 2017

- Apr 26, 2017 Leadership as Idenity Work Apr 26, 2017

- Apr 23, 2017 3 Habits for Bolstering Engagement Apr 23, 2017

- Apr 12, 2017 Encouraging Emergent Leadership Apr 12, 2017

- Apr 12, 2017 Can there really be too much IQ? Apr 12, 2017

-

March 2017

- Mar 13, 2017 The Gathering Influence of Presence Mar 13, 2017

- Mar 10, 2017 3 Things People Want from Coaching Mar 10, 2017

- Mar 8, 2017 The March for Science: A Call for Reasonableness? Mar 8, 2017

- Mar 6, 2017 Poetry & the Meaning of Emotions Mar 6, 2017

- Mar 3, 2017 Leaders Helping Others Cope with Time Pressures Mar 3, 2017

- Mar 1, 2017 How We Use Our Minds at Work: It Changes Mar 1, 2017

-

February 2017

- Feb 14, 2017 Empathy, Engagement, and Leadership Feb 14, 2017

- Feb 2, 2017 Agency: The Vital Center of Leader Action Feb 2, 2017

-

January 2017

- Jan 30, 2017 Leader Identity Development Jan 30, 2017

- Jan 16, 2017 HRD as Action Research Jan 16, 2017

- Jan 11, 2017 Encouraging Emergent Leadership Jan 11, 2017

- Jan 9, 2017 4 Reasons to Approach Leader Development as Identity Work Jan 9, 2017

-

December 2016

- Dec 21, 2016 Why is Mindfulness so Popular? Dec 21, 2016

- Dec 19, 2016 3 Keys to Enduring Emotional Positivity Dec 19, 2016

- Dec 16, 2016 Moral Philosophy for Leaders: A Webinar Dec 16, 2016

- Dec 12, 2016 Making Emerging Leader Development Work Dec 12, 2016

- Dec 12, 2016 Action Learning and Leader Emergence Dec 12, 2016

- Dec 12, 2016 Four Features of Moral Motivation in Leadership Dec 12, 2016

-

November 2016

- Nov 23, 2016 The Reflective Function Nov 23, 2016

- Nov 20, 2016 Agency: a vital aspect of leader identity development Nov 20, 2016

- Nov 17, 2016 Emerging Leader Development Webinar Nov 17, 2016

- Nov 11, 2016 Making Something of Yourself as a Leader Nov 11, 2016

- Nov 3, 2016 Moral versus Moralistic: A vital difference and a role for leaders Nov 3, 2016

- Nov 1, 2016 Leaders' Fidelity to What, to Whom? Nov 1, 2016

-

October 2016

- Oct 29, 2016 Security and Leadership: A Quality Worth Cultivating Oct 29, 2016

- Oct 13, 2016 Good Pride and Bad Pride Oct 13, 2016

- Oct 2, 2016 Three Keys to Organizational Sustainability: Vital Structure, Agency, and Relational Dynamics Oct 2, 2016

-

September 2016

- Sep 19, 2016 Leadership, Leader Development, and the Future of Humankind Sep 19, 2016

- Sep 6, 2016 What Leaders Can Learn From a 3-Year-Old Sep 6, 2016

-

August 2016

- Aug 16, 2016 Contingency and Leader Action Aug 16, 2016

-

July 2016

- Jul 11, 2016 The Paradoxical Effect of Enlightened Self-Reliance Jul 11, 2016

- Jul 2, 2016 Wanted: Courageous Clients Jul 2, 2016

-

June 2016

- Jun 29, 2016 Something Old, Something New: The Johari Window in Relational Coaching Jun 29, 2016

- Jun 22, 2016 The Accidental Struggle Against Happiness Jun 22, 2016

- Jun 18, 2016 Personal Development as Narrowing and as Broadening Jun 18, 2016

- Jun 10, 2016 Founder's Syndrome: Its Impact and Resolution Jun 10, 2016

- Jun 8, 2016 Leadership: Security, Confidence, and Resilience Jun 8, 2016

- Jun 3, 2016 Making Change: Structure, Choices, and Doing Jun 3, 2016

- Jun 2, 2016 Development and Relational Scaffolding Jun 2, 2016

-

May 2016

- May 31, 2016 Leader Identity and Communicative Action May 31, 2016

- May 19, 2016 Getting to the Impact of D & I: What Makes Us Who We Are? May 19, 2016

- May 3, 2016 The Achilles Heel of Development May 3, 2016

-

April 2016

- Apr 13, 2016 When Leaders Make Faces Apr 13, 2016

- Apr 8, 2016 Claiming and Granting Leadership: How It Works Apr 8, 2016

- Apr 5, 2016 Executive Development: Coaching or Therapy? Apr 5, 2016

-

March 2016

- Mar 30, 2016 Living and Leading from a Secure Base Mar 30, 2016

- Mar 23, 2016 Generativity—Its Role in Promoting Leader Development Mar 23, 2016

- Mar 23, 2016 Diversity, Inclusion, and Leader Emergence: What White Males Can Do Mar 23, 2016

-

February 2016

- Feb 29, 2016 Generativity: Why Care? Feb 29, 2016

- Feb 19, 2016 Leadership Presence and Relational Knowing Feb 19, 2016

- Feb 9, 2016 Smart Money Says Promote from Within Feb 9, 2016

- Feb 4, 2016 Creating the Capacity for Teamwork in Real Time Feb 4, 2016

- Feb 3, 2016 Creating Space for Adaptive Action Feb 3, 2016

- Feb 2, 2016 Assessment as Vital Engagement Feb 2, 2016

-

January 2016

- Jan 21, 2016 Connecting the Dots: Fairness, Engagement & Emergent Leadership Jan 21, 2016

- Jan 16, 2016 Practical Ways to Advance Your Leadership in 2016 Jan 16, 2016

- Jan 8, 2016 Why We Expect Arrogance in Leaders Jan 8, 2016

- Jan 4, 2016 The Power of Emergent Leadership Jan 4, 2016

- Jan 1, 2016 Honing Team Dynamics at Home Jan 1, 2016

-

December 2015

- Dec 30, 2015 The Einstein Emotions Dec 30, 2015

- Dec 16, 2015 Onboarding as Performance Management Dec 16, 2015

- Dec 10, 2015 3-Step Solution to Opportunistic Hiring Dec 10, 2015

- Dec 9, 2015 Engagement, Fairness, and Care Dec 9, 2015

- Dec 4, 2015 Real Authenticity & Leadership Dec 4, 2015

- Dec 1, 2015 The Potential to Lead - Part 2 of 3 Dec 1, 2015

-

November 2015

- Nov 30, 2015 A Meditation on Effective Action Nov 30, 2015

- Nov 25, 2015 The Potential to Lead - Part 1 of 3 Nov 25, 2015

- Nov 22, 2015 The Ceiling Effects of IQ in Selection Nov 22, 2015

- Nov 16, 2015 Executive Selection: Getting It Right Nov 16, 2015